Moving Forward

The Ati & Tumandok People of Panay Island

I arrived into Iloilo City on a sunny afternoon with my camera bag and a rough plan as to where I would be going. My research gave me some promising leads, but going on a trip like this is always full of unknowns and surprises. Throughout the past four years I have spent a good amount of time traveling around the Philippine archipelago visiting and learning about different indigenous communities. Project Katutubong Pilipino is a long term personal project I have been dedicated to and feel very strongly about. Over the next couple of weeks I would be devoting my time to both learning and photographing the Ati and Tumandok (also known as the Panay Bukidnon) people on Panay island.

While waiting for Daisy to arrive at the cafe, I couldn’t help but think about some of my past trips. The adventures, sleepless nights, long hikes, peoples smiles, touching personal stories and unbelievable opportunities. As I continue now to explore new areas and communities, it’s hard to imagine what the next stage of Project Katutubong Pilipino will be. There are a number of challenges a project like this brings, both creatively and in finding the needed resources. Although, looking back, it seems the challenges I worry about are almost always somehow overcome. Daisy arrived and we got right into the specifics of where we would be going. Daisy is an anthropologist and she has an excellent relationship with many of the indigenous communities in Panay. After we finished our coffee we headed for the north bus terminal to begin our journey. I grabbed a window seat on the bus, my favorite spot when traveling. The wind began to blow through the window and I made myself as comfortable as could be. It was good to be back in my element. It was time to move forward and see what was ahead.

The Ati are the first people to call Panay Island home. They are genetically related to other Negrito ethnic groups in the Philippines such as the Aeta of Luzon, the Batak of Palawan, the Agta of the Sierra Madres and the Mamanwa of Mindanao.

Human history started in the Philippines when the first people arrived to the islands some 25,000 years ago. Today, these indigenous peoples are known by different names on various islands, but the Spanish classified them generally as “negritos” because of their dark skin. In the western Visayas, the negritos call themselves Ati and can be found primarily on the islands of Panay, Guimaras and Negros. I’ve spent a good amount of time with other negrito groups, mostly in Sierra Madre mountains of Luzon, and I was excited to see what the differences and similarities would be.

(above) An Ati child learning to walk after her mother returns home from the rice fields, Malay, Aklan.

There are still a number of theories as to where the Ati originated from. Some anthropologists hypothesize they are descendants of New Guineans or Australian Aborigines, while others suggest that they came in a wave of migration from Ethiopia. What we do know is the Atis are genetically related to other negrito ethnic groups in the Philippines such as the Aeta of Luzon, the Batak of Palawan, the Agta of the Sierra Madres and the Mamanwa of Mindanao. The word “ati” is a corruption of the Visayan word “agta,” which literally means black.

Today, many Ati communities have adopted western religions but still practice many of their traditional animistic beliefs and rituals carried down from their ancestors.

(above) Ati women leaving their local Baptist church after a Sunday service in the mountains of Panay.

(right) An Ati preacher during Sunday worship. This Ati community adopted Christianity in the 1950’s when an American missionary came to their area. Today this community is 70% Baptist and 30% Pentecostal. Although, there are many Ati communities that have adopted western religions they still practice many of their traditional beliefs and rituals carried down from their ancestors.

The first Ati community I visited about two hours north of Iloilo City was not entirely what I was expecting. It was easily accessible by dirt road and prominent in the middle of the village was a large white Baptist church. After talking with a number of people it was clear that most of the Ati here were now converted Baptists. In fact, I later found out that the majority of Atis in Panay have now been baptized into the Christian religion through various dominations. At some point under Spanish rule a number of Atis became Catholic. Then when the Americans came in the 1950s and 1960s they were converted to Protestantism. I returned to this community a couple of days later for their Sunday service and was again surprised to see the preacher was Ati himself.

(above) Ati children preparing for their first holy communion on Boracay Island. This only remaining Ati community on Boracay is under the care of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. Many of the Ati in this community have now adapted Catholicism.

The Ati have been using herbal medicine since the time they were pure nomadic hunters and gatherers. Overtime, their herbal medicine practices have also taken the form of talismans and amulets which aid in the protection from different spirits.

(above) A wild root crop found in the forests of Guimaras Island which can be eaten or used for medicinal purposes.

(right) Perla Moreno, one of the most knowledgeable herbal medicine elders of the Ati tribe, demonstrates how this particular plant can help reduce a fever or headache, Guimaras Island.

After learning about the Atis adoption of western religion, I thought it would be important to explore some of their more traditional practices. I was pointed in the direction of Guimaras Island where the Atis are known for their herbal medicine practices. In Guimaras, I had the privilege of meeting Perla Moreno who is an herbal medicine expert. We spent an entire day together visiting different sites on the island. During the span of about five hours Perla showed me roughly 40 different plants and described what their medicinal uses were. She showed me everything from cancer healing plants to natural ways to help a common cold. Her knowledge of the local plants was truly inspiring.

A plant called “anino” in the local dialect. The leaves can be used to take away the pain of headaches while the fruit has cancer healing properties.

Various amulets and herbal medicines found in the markets and streets of Iloilo city. These are mostly packaged and sold by the native Ati people as a source of income.

The Ati have been using herbal medicine since the time they were pure nomadic hunters and gatherers. Overtime, their herbal medicine practices have also taken the form of talismans and amulets which aid in the protection from different spirits. Locals will often seek the help of knowledgeable Ati for different medical conditions or to help drive away spirits. In downtown Iloilo city there are a number of small street-side stores where the Ati from Guimaras sell their herbal medicine and amulets to locals. Some of the medicinal healers will also travel to nearby islands to market their products.

(above) Ati elder and herbal medicine expert, Perla Moreno, hiking through the forest on Guimaras Island with her sisiter looking for medicinal plants. During the span of about five hours Perla showed me roughly 40 different plants and described what their medicinal uses were.

(above) An Ati woman waits for customers in front of her small street-side herbal medicine store in downtown Iloilo City.

Throughout their history, hunting has also played a significant role in the life of the Ati people. Wild animals such birds, deer, pigs, turtles, monitor lizards and wild cats were traditionally caught. However, because of deforestation and a more sedentary lifestyle it is becoming harder to hunt and find certain animals. I was told by one Ati hunter that they still prefer wild meat and they still eat it whenever they can to keep a strong body. Assisted by dogs, bows and arrows were the traditional method for hunting larger animals, but today airguns are the popular choice.

Wild animals such as lizards, wild pigs, turtles, wild cats, fish and snails help keep a strong body for the Ati and is still part of their regular diet.

(above) Ati men carry two “bayawak” or monitor lizards which they caught during a morning hunt. Wild animals such as lizards, wild pigs, turtles, wild cats, fish and snails help keep a strong body for the Ati and is still part of their regular diet.

(right) Hunting for monitor lizards requires trained dogs and a lot of patience. The dogs and their owners try to scare the lizards out of the forest to the bank of the river where they can easily be caught.

It was raining for two days straight so the likelihood of finding a lizard was not good. The ideal time to catch a monitor lizard is when they are basking in the sun on the bank of a river. Eager to show me their hunting skills, the men still set off in hopes of finding one. A few hours later three monitor lizards were brought back by the men and their dogs. All three were still alive and cooking immediately began. The alive pregnant lizard was placed on the fire first to char its skin before the meat was removed to be cooked in an adobo sauce. Because this is ancestral domain, the Ati are allowed to hunt and eat whatever animals they find. Non-Ati are not legally allowed to hunt or eat monitor lizards.

(above) A monitor lizard being cooked over an open fire. After the lizard has been partially cooked the meat is removed and cooked again in some type of sauce. This particular lizard had eggs inside which were also eaten.

With cultural lines slowly becoming more obsolete it’s easy to see that languages, such as Inati, will overtime be another unspoken language.

(above) Ati youth enjoying a small river which passes through their community. In 2009, during heavy rainfall, five children got caught on the rocks just upstream from where this photo was taken because to the raising river water. The children were unable to escape and people could not hear their cry for help. All of them drowned that day. Three of the five were siblings.

(right) An Ati teenager. Fairly self-conscious about her hair, it took me some time to convince her to let it down for the photo. Many Atis are now integrating more and more with lowland communities and mixed blood is very common. In fact, in certain Ati communities, it can be difficult to distinguish their facial characteristics from other non-Ati communities.

I have been to a number of other negrito groups mostly in Luzon and one in Mindanao. For me, the Atis seem more integrated with lowlanders than with the other negrito groups I have visited. Likewise, the Atis seem to have more intermarriages and therefore mixed blood. At times, it was difficult to even visually tell I was in an Ati community. They speak a language called Inati, although the youth now prefer to speak the regional dialects of either Ilonggo, Aklanon or Kinaray-a. With cultural lines slowly becoming more obsolete it’s easy to see that languages, such as Inati, will overtime be another unspoken language.

(above) Ati girls arrive back in their village after competing in a local softball tournament. Many of the the indigenous Ati are now integrating more into typical Filipino/adapted western culture, especially the younger generation. In the distance, you can see Boracay Island.

(right) Preparing to take the field during the weekend local softball tournament.

In many ways it was inspirational to see Atis integrating more into local Filipino/adapted western culture. Typically, my time with indigenous peoples in the Philippines revolves around rural life and those everyday activities away from the city. It was certainly a nice change to see IP’s being accepted and taking on different roles. Although, there is still plenty of discrimination against the Ati, because of their darker skin color, more and more are finding their place in modern society. I heard a number of stories about Atis landing jobs abroad after college or those who now work as teachers or in hospitals. It’s encouraging to see and hear these stories.

An Ati leader in Antique province volunteers regularly at the local barangay health center. Here she helps file papers and does small tasks for patients. She is an active and well respected member of her community.

A young Ati man working as a housekeeper at a hotel in Iloilo City. It’s still fairly uncommon to see Atis working ‘regular’ city jobs, but more and more Atis are finishing their primary education. I met a number of Ati youth who were either in college or recently graduated and looking for work. This hotel employs two Atis.

It’s still fairly uncommon to see Atis working ‘regular’ city jobs, but more and more Atis are finishing their primary education. I met a number of Ati youth who were either in college or recently graduated and looking for work.

(above) Everyday, materials such as food, water, fresh produce and construction goods are loaded into boats on mainland Aklan and shipped to Boracay. The loading of boats provides a livelihood for many Ati families living nearby in Malay, Aklan.

(right) Ati men load pineapples into boats heading for the resort island of Boracay.

In Aklan province, many Ati men work as laborers around the tourism industry of Boracay. Everyday, materials are shipped to Boracay from the mainland on small barges and outrigger boats. The loading of materials provides a livelihood for many Ati families living nearby. It is also common for many Ati men to work as sugar cane harvesters during harvest season in Panay and in neighboring Negros island. Likewise, Atis also can be found working as wage laborers for landowners permanent rice cultivation. Ati women will often generate additional income by making handicrafts, working as house help or raising animals to sell.

(above) Men loading construction materials into boats which will be shipped across the short channel from mainland Aklan to Boracay island. Ati men make up a large percentage of this manual labor workforce supporting the daily needs of Boracay.

The Ati were the original inhabitants of Boracay Island, long before the Philippines was colonized. Over time, and especially during the last 50 years, they have been slowly displaced by the proliferation of more and more resorts, restaurants, hotels and shopping centers.

(above) Boracay’s white sand beaches draw millions of local and foreign tourists every year.

(above) Boracay is a favorite tourist destination for both Filipinos and foreigners, reaching nearly 1.5 million visitors in 2014. The main attraction in Boracay is its white sand beach and clear water. The Ati used to call all of Boracay island their home, but today their land has been reduced to a mere 2.1 hectares.

(right) There are roughly 40 Ati families living on the remaining small 2.1 hectare piece of ancestral land and they are still harassed by private commercial interests who continue to claim ownership over the same lot of land. Their homes are now uniform shelters which were built by the sisters under the Daughters of Charity.

It had been 8 years since I was last in Boracay. It’s not a destination I often find myself in as I prefer the more quite and low key vacation spots. For those readers who are not familiar with Boracay, it is probably the most popular destination within the Philippines for vacations, partying and resorts. However, this trip to the famous island would be different for me, as I would be visiting the last remaining Ati community still present there. The whole of Boracay island was once originally home to the Ati people even long before the Spanish arrived centuries ago. After the tourism boom started in the 1970’s the Atis have been slowly pushed aside and today only occupy 2.1 hectares of the islands total 1,032 hectares.

(above) Chinese tourists pose with an Ati child in Boracay. The Ati community here gets a number of visitors, mostly asian tourists looking to have their photos taken together with the Ati children. There is also a small on-site heritage house where visitors can learn about the Ati people.

Mainly because of discrimination and lack of support, the Atis on Boracay are not as integrated into the larger community as are many of the Atis on the mainland. Only a small percentage of them work in the numerous hotels and restaurants on the island and some end up resorting to begging.

Ati children play on the coastline in front of their Boracay ancestral domain. This is considered some of the most expensive real-estate in the country.

Mainly because of discrimination and lack of support, the Atis on Boracay are not as integrated into the larger community as are many of the Atis on the mainland. Only a small percentage of them work in the numerous hotels and restaurants on the island and some end up resorting to begging. In February 2013, Dexter Condez, the spokesman of the Boracay Ati community was shot and killed because of his advocacy for his tribe and their rights. Dexter was the only Ati at the time educated enough to represent his people on the claim of land in Boracay. Although the security guard who killed him was caught, nothing has been done to the larger criminal who hired the guard to carry out the murder. Tourists who visit the island remain largely oblivious to the issues surrounding the Ati, which usually remain hidden from public view.

The murder of Dexter, although tragic, will hopefully continue to fundamentally change the Atis place in Boracay. There are a number of foundations now helping the Ati and with some more support from the government the Ati could again revitalize themselves as a people on the island. If done right, I also believe there could be some significant tourism potential for the Ati. Perhaps something along the lines of livelihoods, promoting education of their culture with more genuine experiences for their visitors. Then perhaps the Ati would feel more proud of their culture and would want to share it with others. It’s a complicated issue, but I always think openness is the best way forward and nothing should ever be forced upon a community.

A group of students from a local university volunteer and carry out an activity for the Ati children in Boracay. This group distributed food and drinks for the children.

(above) An Ati adolescent playing with a tire and piece of driftwood on the beach in front of his ancestral domain on Boracay Island.

(above) Women talking in front of their homes in Malay, Aklan. This Ati community is staying on a plot of land donated by charity because they do not yet have declared ancestral domain to settle on.

I was fortunate enough to meet the outspoken and charming leader of the Ati people in Aklan, Vicente Ilorde, during my visit. He was in the Malay community to conduct a meeting with his people regarding the process of claiming ancestral domain. The process itself will take many years, but Vicente is one hundred percent behind the idea and he wants to push forward with it. This was the preliminary meeting to map out households and discuss the process with the community. Seeing that there is very little approved ancestral domain for the Ati people in Aklan, this would be a huge step forward for Vicente and the Ati there.

Vicente Ilorde, the Ati Chieftain, leads a meeting with his community to discuss the preliminary stages of filing for certified ancestral domain in Malay, Aklan. Maps were drawn to show where each family stays in relation to the area they will be applying for. Currently, the only approved ancestral domain for the Ati in the entire province of Aklan is the 2.1 hectares on Boracay Island. The latest population census of Ati in Aklan is 22,837.

The mountains of Panay Island. The Ati can be found in the Panay provinces of Aklan, Capiz, Antique, Iloilo and Guimaras. As of 2013, the total approved and certified ancestral domain for all of Panay Island, including Guimaras, was 8,177.7 hectares. This equates to roughly 0.6% of these islands total land area.

Currently, the only approved ancestral domain for the Atis in the entire province of Aklan is the small 2.1 hectares on Boracay Island, with the latest population census of Atis in Aklan being 22,837.

(above) Community members gather for their first meeting to discuss the process of applying and acquiring ancestral domain in Malay, Aklan.

Although life is changing, subsistence farming and working with the land is still the primary activity for the majority of Ati. Permanent rice and corn cultivation has replaced traditional hunting and shifting agriculture practices. At the same time, the issues that many indigent Filipinos face are the same concerns for the Atis, such as access to clean water, sanitation and medical care. We were fortunate to be able to give 12 water filters to the community (provided by Waves for Water) in Malay, Aklan because all of their water sources tested positive for bacteria.

Historically, the Atis were nomadic and would rely on gathering wild foods, especially fruits, tubers, roots and honey. This lifestyle is now mostly abandon due to deforestation and pressure from lowland population.

(above) Rice being cooked over fire in what is called a ‘dirty kitchen.’ This method of cooking is still the most common way to cook food for many in rural Philippines including the Atis.

(right) An Ati man carrying banana leaves which will be used in the process to make charcoal. Today, charcoal making is a very common livelihood for many of the Atis.

Corn being cooked on an open fire. Many Atis now engage in some type of agriculture, mostly subsistence farming. Historically, the Atis were nomadic and would rely on gathering wild foods, especially fruits, tubers, roots and honey. This lifestyle is now mostly abandon due to deforestation and pressure from lowland population. Often their subsistence farming is not enough for their family needs and other livelihood income generation is necessary.

(above) Portrait of an Ati farmer.

There are a number of historical practices and Filipino traditions that trace back to the Ati people. Negros island was named by the Spanish after the Ati people, something I did not know prior to this trip. Likewise, the origin of the popular Ati-Atihan festival in Kalibo was a non-religious celebration by the Atis in thanksgiving for gifts they had been given by lowlanders. Today, the festival is celebrated as a religious festival. The history of the Ati people is rich, like the other negrito groups in the country. After all, Philippine history starts with them. They have been marginalized and taken advantage of often throughout their history as a people and I can only hope future generations never forgot this as things progress. I think this Ati song is appropriate. Though we be Negritos, of the black race, here were we born. Our worth is as of diamond, most precious diamond from two ancestral lines. We precede the Bisayans, as we did the Spaniards. Spaniards in Manila, priests in Iloilo had broken the agong, had cracked the bell. Bell, you peal. Agong, you toll

“Though we be Negritos, of the black race, here were we born. Our worth is as of diamond, most precious diamond … we precede the Bisayans, as we did the Spaniards.”

(above) An impromptu Pagabuhitan dance, a traditional livelihood dance done by the Atis. Because the Atis were historically nomadic they do not have as many rituals or customary dances like other tribes in the Philippines.

(right) An Ati woman near her home in Malay, Aklan. The typical home of an Ati family is made from natural materials sourced from the forest. Those families who are more well off will opt for a cement foundation in their home.

Portrait of an Ati child in Iloilo province.

Another indigenous group apart from the Atis reside in the Capiz mountains of Panay. They often refer to themselves as the Tumandok or Suludnon, but are also also known as the Panay Bukidnon tribe. They are the only indigenous group to traditionally speak a Visayan language. Although they were once culturally related to the lowland inhabitants of Panay, their isolation from Spanish rule resulted in the continuation of pre-Hispanic culture and beliefs. The Panay Bukidnon are known for their detailed embroidery and for their epic chants which depict stories from their history as a people. The Panay Bukidnon are also known for a tradition, which is no longer practiced today, of creating well-kept maidens called Binukots starting at a young age.

(above) Rolando Caballero helps guide his wife, Pricilla Caballero, who is the last known Binukot of the Panay Bukidnon Tribe in central Panay.

Traditionally, the Binukot is isolated by her parents from the rest of the household at 3 or 4 years of age. She is not exposed to the sun, not allowed to work, and is even accompanied by her parents when she takes a bath. This results in a fair, frail, fine-complexioned and long-haired woman. As she stays at home most of the time, her parents and grandparents entertain her with various oral lores and traditional dances. This makes the Binukot excellent epic chanters and repositories of their history. Tradition persists that the Binukot must not be seen by any man from childhood until puberty. Only the family members and the female servants may come face to face with her. In order to keep her away from mens eyes, as well as shield her from the sun, she bathes in the river in the evening. A makeshift enclosure may also be made for her in the river for this purpose. No man actually would dare to look at a Binukot as there was a threat of punishment by death to anyone who would violate her by looking. Today, the practice no longer happens.

Photos of Rolando and Pricilla Caballero displayed in a community building. The couple saw each other for the first time on their wedding day. Rolando’s family paid a large dowry of cash and one water buffalo for the honor of their son to marry Pricilla.

Pricilla Caballero, now blind, is still well taken care of by her family. From the time she was a young child until her wedding day, Pricilla Caballero was kept from the public eye, secluded to her home and rarely exposed to the sun.

(above) Portrait of Pricilla Caballero, the last Binukot.

Tradition persists that the Binukot must not be seen by any man from childhood until puberty. Only the family members and the female servants may come face to face with her.

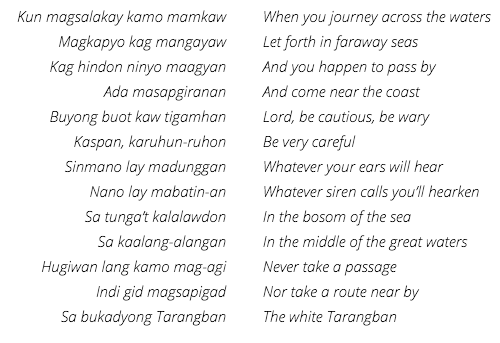

Still present today in Panay Bukidnon culture is the Suguidanon or the telling of a story through chanting an epic narrative in a particular tone and timbre. The tribe has 10 epics that contain details of heroic deeds and significant events relevant to their culture. Traditionally, these epics are sung as lullabies to children at bedtime, while waiting for time to pass or during special gatherings. They were memorized by the tribe, especially by the Binukots of the community. Today, most of the epics have been recorded and transcribed by historians and the elders of the tribe.

The Panay Bukidnon’s 10 epic chants tell stories about legendary warriors and significant events relevant to their culture and history and can sometimes take days to completely chant one epic.

(above) Romulo Caballero, a Panay Bukidnon elder, chanting a portion of an epic. The tribe’s epics, or oral poetry, is transmitted primarily through chanting. The epic chants tell stories about their legendary warriors and history and can take days to completely chant one epic, all from memory. Their longest epic is called Hinilawod and is considered the world’s longest known epic alongside that of Tibet’s Epic of King Gesar. Hinilawod is a 28,000-verse epic that takes about three days to chant in its original form (Wiki).

(right) Every Saturday, class is held in a small building which they call the ‘School for Living Tradition.’ Here the tribe’s elders teach the children about their history, the tribe’s lores, dances and their epic chants. During weekdays children attend regular public school. Below this photo is a short excerpt from the epic Humadapnon.

(above) A young Panay Bukidnon girl performing one of the tribes traditional dances. These dances are also learned at the School for Living Tradition.

(right) A Panay Bukidnon girl during class at the School for Living Tradition. Behind her are verses from an epic written on a chalkboard. Many of the tribe’s epic chants have now been recorded in writing.

For more in-depth information on the Ati and Panay Bukidnon the Center for West Visayan Studies in Iloilo is a great resource. Likewise, I must give my utmost thanks to Daisy Yanson who arranged, translated, provided research and access to communities and who traveled with me during my time in Panay. If anyone is in need of someone like Daisy, I wouldn’t recommend anyone else.

email: [email protected] |

© 2026 Jacob Maentz